Málþing á vegum Miðaldastofu Háskóla Íslands — A University of Iceland Centre for Medieval Studies Symposium

Föstudaginn 25. október 2024 kl. 14.00-16.30 — Friday, October 25, 2024, at 14.00-16.30

Fyrirlestrasal Eddu — Edda auditorium

Dagskrá — Program:

14.00-14.30 Miriam Conti, University of Bergen: The jigsaw of Alvíssmál: false fits of textual transmission

14.30-15.00 Yulia Osovtsova, University of Stavanger: Snorri the architect: Prosimetrical creation of the mythological universe

15.00-15.30 Kaffihlé — Coffee Break

15.30-16.00 Bianca Patria, University of Oslo: How to Kill a Dwarf: Snorri, the Mead of Poetry and a Late Kenning Type

16.00-16.30 Nelson Goering, University of Oslo: Type A Verses with Light Second Lifts in Beowulf: Reviewing the Evidence

Málþingið fer fram á ensku og er öllum opið. — The symposium will be conducted in English. All are welcome to attend.

Miðaldastofa Háskóla Íslands — The University of Iceland Center for Medieval Studies

—o—o—o—

Miriam Conti

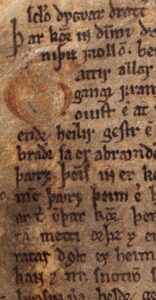

The jigsaw of Alvíssmál: false fits of textual transmission

Alvíssmál is a puzzling poem in many different ways. It has a relatively rigid and repetitive structure, and the narrative frame is rather subsidiary. Its main scope is to provide poetic synonyms about earthly and heavenly matters, rather than tell an original mythological episode.

It is also interesting with regard to intertextuality, as Snorri quotes stanzas 20 and 30 in Skáldskaparmál. There are, however, remarkable lexical and, sometimes, syntactical inconsistencies between the Poetic and the Prose Edda, not least within the different manuscripts of Snorra Edda. In order to better understand the process of transmission of this poem, it is necessary to consider such differences singularly.

This paper will focus on a selection of the textual inconsistencies between stanzas 20 and 30 of Alvíssmál between the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda and the witnesses of Snorra Edda, and whether those can be attributed to different oral traditions or be the result of scribal transmission.

Miriam Conti is a Ph.D. student at the University of Bergen, working on a thesis about the prehistory and intertextuality of Eddic poetry. Her background is in linguistics (Sapienza University of Rome) and Old Norse philology (University of Oslo). Her interests include textual criticism, historical linguistics, Latin influence in Old Norse, and language acquisition.

—o—o—o—

Yulia Osovtsova

Snorri the architect: Prosimetrical creation of the mythological universe

The famous medieval Icelandic handbook on poetics called Edda, traditionally dated to the years 1221–25, takes a central position within the corpus of Old Norse literature. It often serves as the first introduction to the world of Old Norse mythology and poetry. Despite being a medieval work written some two hundred years after Iceland’s Christianization, Snorra Edda, and Gylfaginning specifically, remain our main sources to Norse mythology.

In Gylfaginning, Snorri quotes a large number of eddic stanzas, which have the purpose to corroborate the account given in prose. The poetry thus receives an auxiliary function in the overall structure of the text – the stanzas are generally inserted to provide evidence to Snorri’s narrative. At the same time, they are presented as authentic and as the source of traditional knowledge, which is transmitted in prose in Gylfaginning.

The treatise thus bears witness to Snorri’s reception and interpretation of poetry, both of its form and content. However, since Snorra Edda is generally considered as an important source to Norse mythology, there is a strong tendency to interpret the myths and allusions to myths found in eddic and skaldic poetry in accordance with Snorri’s narratives. In my opinion it is crucial to analyse Snorri’s attitude to poetic tradition and to examine his method of prosimetrical composition in order to get a better understanding of the lens through which we tend to approach Old Norse tradition.

The presentation will focus on Snorriʼs method of prosimetrical composition in Gylfaginning. The overarching question will be: How did Snorri use identifiable poetic sources in order to create the mythological universe we find in his work? Moreover, it will be demonstrated how his attempt to align Old Norse myths with the Biblical narratives enabled him to construct non-existent connections between mythical creatures and places, which had a significant impact on the mythological topography presented by him in Gylfaginning. The famous world tree, Yggdrasill, found in the centre of this universe, will provide a great case study to exemplify Snorriʼs method.

Yulia Osovtsova is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Stavanger. She holds an MA in Viking and Medieval Studies from the University of Oslo (2021) and is a member of the research project Old Norse poetry and the development of saga literature. Her research interests are Old Norse poetry and grammatical literature, as well as Snorra Edda.

—o—o—o—

Bianca Patria

How to Kill a Dwarf: Snorri, the Mead of Poetry and a Late Kenning Type

We are all familiar with Snorri Sturluson’s account of the mead-of-poetry myth in Skáldskaparmál: the inspiring drink is brewed by the dwarfs Fjalarr and Galarr from the blood of the wise being Kvasir and it passes from hand to hand, by means of trickery or violence, until it is eventually obtained by Óðinn. Several details of this complex story are attested in eddic and skaldic sources. A survey of the kennings for ‘poetry’ reveals, however, an interesting distribution: while most of the other creatures named by Snorri are attested in datable early sources, the dwarfs Fjalarr and Galarr are less securely attested in poems composed before the late twelfth century. In early verse, dwarfs and poetry seem to be connected only in a few and textually dubious cases. After c. 1150, by contrast, ‘the mead of the dwarf[s]’ suddenly becomes a widespread kenning-type, but is found in fully Christian, learned and antiquarian poems such as Rekstefja, Snæfríðardrápa and Íslendingadrápa. This kenning type is prescribed in Skáldskaparmál, however, and this has influenced not only the later poetic tradition (including rímur), but also editorial readings and interpretations. By means of a critical evaluation of the datable poetic evidence, this talk suggests that dwarfs were not involved in Viking Age versions of the mead-of-poetry story.

Bianca Patria is a postdoctoral fellow in Old Norse Philology at the Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies, University of Oslo. Her interests include Old Norse and Germanic poetry, historical linguistics and metrics, while her research focuses mainly on the diction of skaldic poetry.

—o—o—o—

Nelson Goering

Type A Verses with Light Second Lifts in Beowulf: Reviewing the Evidence

The most frequent verse pattern in Beowulf is what Sievers labeled type A, with the stress contour SwSw (strong-weak-strong-weak), that is, with a roughly trochaic rhythm. Normally the two metrical prominences (lifts, S-positions) are both either heavy syllables or a resolved sequence of a light syllable plus some other syllable. There are well over 2000 half-lines of this type (roughly a third of all verses in the poem). The second lift can only be filled with a light syllable on its own if the position before it is also stressed: SsS̆w (type A2k). There are, however, perhaps type A six verses in Beowulf that seem to show a light second lift, SwS̆w, unprompted by any normal condition that would allow suspension of resolution: 719a, 845a, 881a, 954a, 1828b, and 2430b. The last of these, Hrēðel cyning “king Hrethel” exemplifies the type. There are also six examples of possible light lifts in type A3 verses (wwS̆w).

For three of the type A verses, the standard editions generally adopt alternate readings (719a) or posit archaic/dialectal linguistic variants (881a, 1828b) that result in the second lift scanning as heavy after all. But the other three are often accepted as valid, if rare, metrical variants (e.g. Fulk, Bjork, & Niles 2008: 330; Pascual 2013: 56). I propose instead that two old emendations should be revived and adopted in 845a (ofer·wunnen for ofer·cumen, Kaluza 1894: 82) and 954a (ge·fēred for ge·fremed, Andrew 1948: 138), which would provide these verses with heavy second lifts as well (the latter example is also supported on non-metrical grounds). In the interest of time, the type A3 verses will not be considered in detail, but they too can be treated similarly.

This leaves only 2430b, long recognized as metrically problematic, to stand as an example of a possible light second lift. How this anomalous verse should be viewed depends on one’s general views of textual criticism. It could be emended as well, but only through a more interventionist reordering of several words. Alternatively, an exceptional and linguistically unmotivated second stress has been posited for the second syllable of Hrḗðèl, eliminating the metrical anomaly but introducing a linguistic anomaly. However this verse is approached, it is isolated and cannot serve as reasonable evidence for the theory that the Beowulf-poet accepted light second lifts.

Nelson Goering is an MSCA postdoc at the University of Oslo, previously of Ghent and Oxford (where he received a DPhil in comparative philology and general linguistics). He works on the phonology of early Germanic. His open-access monograph Prosody in Medieval English and Norse is available from Oxford University Press.

—o—

Málþingið fer fram á ensku og er öllum opið.

The symposium will be conducted in English. All are welcome to attend.

Miðaldastofa Háskóla Íslands — The University of Iceland Center for Medieval Studies